Latest:

Homo naledi: New species of human ancestor discovered in South Africa

By David McKenzie and Hamilton Wende, CNN Updated 1740 GMT (0040 HKT) September 10, 2015 | Video Source: CNN Updated 1740 GMT (0040 HKT) September 10, 2015 | Video Source: CNN

JUST WATCHED

Homo naledi: Scientists find ancient human relative

Rising Star Cave, South Africa (CNN) When an amateur caver and university geologist arrived at Lee Berger’s house one night in late 2013 with a fragment of a fossil jawbone in hand, they broke out the beers and called National Geographic.

Berger, a professor at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, had unearthed some major finds before. But he knew he had something big on his hands.

What he didn’t know at the time is that it would shake up our understanding of the progress of human evolution and even pose new questions about our identity.

Two years after they were tipped off by cavers plumbing the depths of the limestone tunnels in the Rising Star Cave outside Johannesburg, Berger and his team have discovered what they say is a new addition to our family tree.

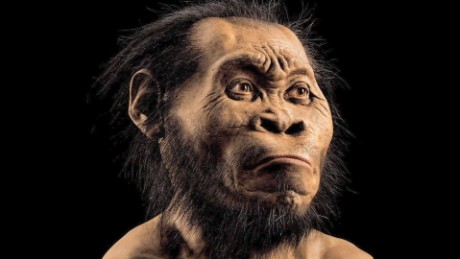

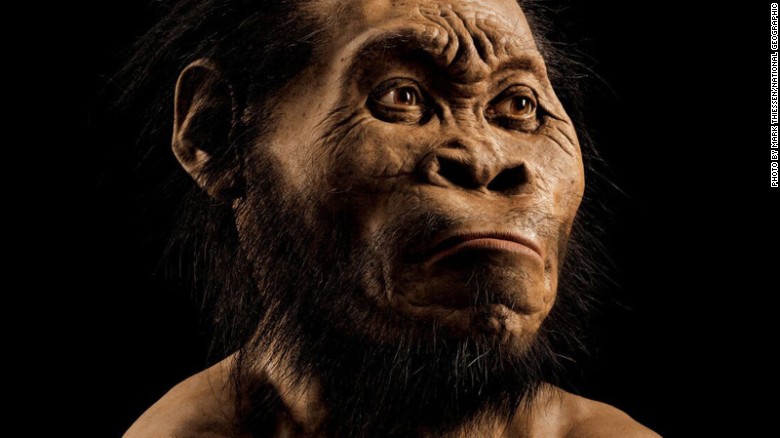

The team is calling this new species of human relative “Homo naledi,” and they say it appears to have buried its dead — a behavior scientists previously thought was limited to humans.

Berger’s team came up with the startling theory just days after reaching the place where the fossils — consisting of infants, children, adults and elderly individuals — were found, in a previously isolated chamber within the cave.

The team believes that the chamber, located 30 meters underground in the Cradle of Humanity world heritage site, was a burial ground — and that Homo naledi could have used fire to light the way.

“There is no damage from predators, there is no sign of a catastrophe. We had to come to the inevitable conclusion that Homo naledi, a non-human species of hominid, was deliberately disposing of its dead in that dark chamber. Why, we don’t know,” Berger told CNN.

“Until the moment of discovery of ‘naledi,’ I would have probably said to you that it was our defining character. The idea of burial of the dead or ritualized body disposal is something utterly uniquely human.”

Standing at the entrance to the cave this week, Berger said: “We have just encountered another species that perhaps thought about its own mortality, and went to great risk and effort to dispose of its dead in a deep, remote, chamber right behind us.”

“It absolutely questions what makes us human. And I don’t think we know anymore what does.”

The first undisputed human burial dates to some 100,000 years ago, but because Berger’s team hasn’t yet been able to date naledi’s fossils, they aren’t clear how significant their theory is.

Berger tried to put the new find into perspective.

“This is like opening up Tutankhamen’s tomb,” he said. “It is that extreme and perhaps that influential in this stage of our history.”

Link/Photos/Video: http://edition.cnn.com/2015/09/10/africa/homo-naledi-human-relative-species/index.html

Science

New Species of Human Ancestor Is Found in a South African Cave

Acting on a tip from spelunkers two years ago, scientists in South Africa discovered what the cavers had only dimly glimpsed through a crack in a limestone wall deep in the Rising Star cave: lots and lots of old bones.

The remains covered the earthen floor beyond the narrow opening. This was, the scientists concluded, a large, dark chamber for the dead of a previously unidentified species of the early human lineage — Homo naledi.

The new hominin species was announced on Thursday by an international team of more than 60 scientists led by Lee R. Berger, an American paleoanthropologist who is a professor of human evolution studies at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. The species name, H. naledi, refers to the cave where the bones lay undisturbed for so long; “naledi” means “star” in the local Sesotho language.

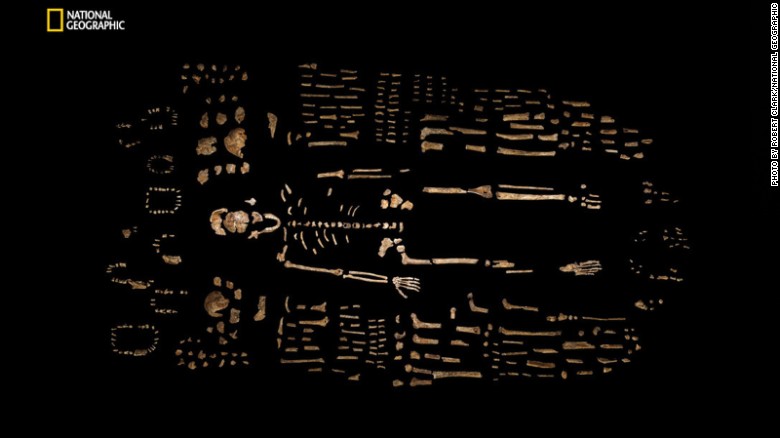

In two papers published this week in the open-access journal eLife, the researchers said that the more than 1,550 fossil elements documenting the discovery constituted the largest sample for any hominin species in a single African site, and one of the largest anywhere in the world. Further, the scientists said, that sample is probably a small fraction of the fossils yet to be recovered from the chamber. So far the team has recovered parts of at least 15 individuals.

“With almost every bone in the body represented multiple times, Homo naledi is already practically the best-known fossil member of our lineage,” Dr. Berger said.

Besides introducing a new member of the prehuman family, the discovery suggests that some early hominins intentionally deposited bodies of their dead in a remote and largely inaccessible cave chamber, a behavior previously considered limited to modern humans. Some of the scientists referred to the practice as a ritualized treatment of their dead, but by “ritual” they said they meant a deliberate and repeated practice, not necessarily a kind of religious rite.

“It’s very, very fascinating,” said Ian Tattersall, an authority on human evolution at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, who was not involved in the research. “No question there’s at least one new species here,” he added, “but there may be debate over the Homo designation, though the species is quite different from anything else we have seen.”

More Reporting on Human Origins

The Human Family Tree Bristles With New Branches

-

Jawbone Fossil Fills a Gap in Early Human Evolution

-

Siberian Fossils Were Neanderthals’ Eastern Cousins, DNA Reveals

-

Teeth of Human Ancestors Hold Clues to Their Family Life

-

Some Prehumans Feasted on Bark Instead of Grasses

-

Genetic Data and Fossil Evidence Tell Differing Tales of Human Origins

A colleague of Dr. Tattersall’s at the museum, Eric Delson, who also is a professor at Lehman College of the City University of New York, was also impressed, saying, “Berger does it again!”

Dr. Delson was referring to Dr. Berger’s previous headline discovery, published in 2010, also involving cave deposits at the Cradle of Humankind site, 30 miles northwest of Johannesburg. He found many fewer fossils that time, but enough to conclude he was looking at a new species, which he named Australopithecus sediba. Geologists said the individuals lived 1.78 million to 1.95 million years ago, when australopithecines and early species of Homo were contemporaries.

Researchers analyzing the H. naledi fossils have not yet nailed down their age, which is difficult to measure because of the muddled chamber sediments and the absence of other fauna remains nearby. Some of its primitive anatomy, like a brain no larger than an average orange, Dr. Berger said, indicated that the species evolved near or at the root of the Homo genus, meaning it must be in excess of 2.5 million to 2.8 million years old. Geologists think the cave is no older than three million years.

The field work and two years of analysis for Dr. Berger’s latest discovery were supported by the University of the Witwatersrand, the National Geographic Society and the South African Department of Science and Technology/National Research Foundation. In addition to the journal articles, the findings will be featured in the October issue of National Geographic Magazine and in a two-hour NOVA/National Geographic documentary to air Wednesday on PBS.

Scientists on the discovery team and those not involved in the research noted the mosaic of contrasting anatomical features, including more modern-looking jaws and teeth and feet, that warrant the hominin’s placement as a species in the genus Homo, not Australopithecus, the genus that includes the famous Lucy species that lived 3.2 million years ago. The hands of the newly discovered specimens reminded some scientists of the earliest previously identified specimens of Homo habilis, who were apparently among the first toolmakers.

At a news conference on Wednesday, John Hawks of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, a senior author of the paper describing the new species, said it was “unlike any other species seen before,” noting that a small skull with a brain one-third the size of modern human braincases was perched atop a very slender body. An average H. naledi was about five feet tall and weighed almost 100 pounds, he said.

Tracy Kivell of the University of Kent, in England, an associate of Dr. Berger’s team, was struck by H. naledi’s “extremely curved fingers, more curved than almost any other species of early hominin, which clearly demonstrates climbing capabilities.”

William Harcourt-Smith of Lehman College of the City University of New York, a researcher at the American Museum of Natural History, led the analysis of the feet of the new species, which he said are “virtually indistinguishable from those of modern humans.” These feet, combined with its long legs, suggest that H. naledi was well suited for upright long-distance walking, Dr. Harcourt-Smith said.

In an accompanying commentary in the journal, Chris Stringer, a paleoanthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London, found overall similarities between the new species and fossils from Dmanisi, in the former Soviet republic of Georgia, dated to about 1.8 million years ago. The Georgian specimens are usually assigned to an early variety of Homo erectus.

Human Family Tree