Latest:

A tree for Nohemi: Family and friends mark year since Long Beach student’s death in Paris attack

Family and friends who gathered at Cal State Long Beach on Sunday grew emotional as they remembered the life of Nohemi Gonzalez, the only American killed in the Paris terror attacks last November.

A year had passed since the 23-year-old’s death while studying abroad at the Strate School of Design in Paris. She was one of 130 people killed in the bombing and shooting rampage on Nov. 13, 2015.

More: http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-terror-attack-anniversary-20161113-story.html

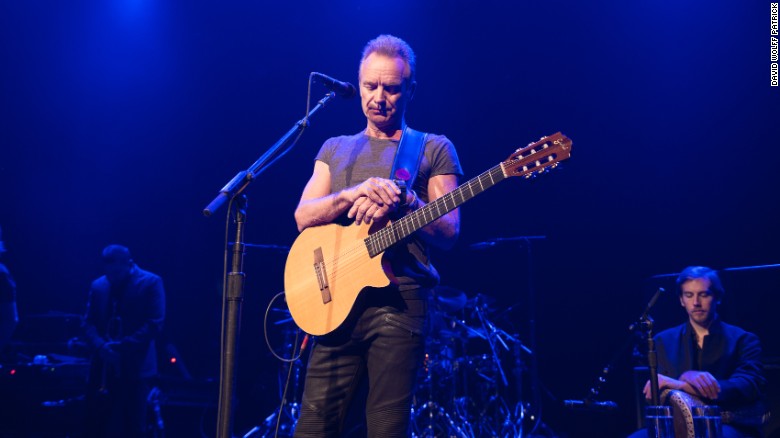

Sting reopens Bataclan after Paris terror attacks

By Melissa Bell and Saskya Vandoorne, CNN Updated 1056 GMT (1856 HKT) November 13, 2016

More: http://edition.cnn.com/2016/11/13/europe/paris-bataclan-sting/index.html

http://edition.cnn.com/2016/11/13/europe/paris-attacks-one-year-on/index.html

**************************

Paris attack, a year later: Daughter’s death still seems surreal to mom

A couple remembers Southern California student Nohemi Gonzalez, slain by terrorists a year ago in France.

Tucked in the corner of a Norwalk shopping center, there’s a barbershop that’s been touched by terrorism.

Inside among the 10 or so hairstyling stations is where Betty Gonzalez learned her daughter had been shot to death by jihadist gunmen.

It’s where President Barack Obama called to give his condolences while customers still sitting in black-leather barber chairs listened to his voice on speaker phone. And it’s where Gonzalez and her husband of four years, Joe Hernandez, keep alive the memory of Nohemi Gonzalez.

Tacked above mirrors that line the shop’s gray walls are poster-sized photos of 23-year-old Nohemi. Mixed in are smaller snapshots with friends, formal proclamations of mourning from state officials and a banner packed with handwritten messages from Nohemi’s fellow students at Cal State Long Beach.

Nohemi’s name became famous last year as the only American killed during the Nov. 13, 2015, terrorist attacks in Paris. She was dining at the cafe La Belle Equipe during a semester of studying abroad when gunmen sprayed the bistro with bullets, killing 19 people. After more coordinated violence, including suicide bombings at the Stade de France stadium where a soccer match was underway and a shooting massacre at the Bataclan concert hall, 130 people were dead.

One year later, France continues to grapple with the aftermath of the attacks carried out by militants from the self-proclaimed Islamic State.

After a massive months-long manhunt, the nation is awaiting trial for Salah Abdeslam, a Belgian-born French citizen charged with participating in the attacks.

A state of emergency that gives police expanded powers to search homes and detains suspects remains in place.

And citizens have had to confront questions of security as terror again rocked the nation on July 14 when an assailant drove a truck through a crowd celebrating Bastille Day in Nice, killing 86.

In Norwalk, the attack’s after-effects don’t have the same scale, but they are pointed and purely personal.

As the anniversary approached this week, hairdressers arrived as normal to set up their stations, and clients wandered in looking for a trim.

But on a couch in the shop’s tiny back room, squeezed in between her husband and the employee fridge, Betty at times seemed distant as she described how her life has changed since her daughter’s death.

“Every day it’s the same,” she said. “I still can’t believe what happened to her.”

Occasionally she wiped away a tear, careful not to muss the makeup she just put on in one of the shop’s mirrors.

“Even though it’s going to be a year, I think it’s still fresh,” Hernandez said. “We can still remember like it was yesterday.”

The fateful evening

The evening of Nov. 13, Hernandez – who is Nohemi’s stepfather – and Betty were working at their shop when Betty got a call from a friend telling her to turn on the news.

Betty did, but she only watched it fleetingly. She wasn’t worried about her daughter, even though the study abroad trip was her first out of the country.

Nohemi was a cautious girl, she thought, never one to put herself in danger and always quick to learn from others’ mistakes.

But later that night, Nohemi’s boyfriend arrived at the shop’s front door and waved for Hernandez to come over.

More: http://www.pe.com/articles/nohemi-818345-betty-hernandez.html

********************

In Memoriam

Djamila Houd, 41 ans

Elle a été tuée sur la terrasse de La Belle équipe, le restaurant de son mari, Grégory Reibenberg, où elle fêtait un anniversaire avec des amis. Elle est morte dans les bras de son mari. « Je lui tenais la main, on ne pouvait pas la ranimer, on ne pouvait plus rien faire (…). Elle m’a demandé de prendre soin de notre fille et je lui ai promis de le faire », a-t-il témoigné sur France 2 . Le couple a une fille de 8 ans. La victime, originaire de Dreux (Eure-et-Loir), travaillait pour une entreprise de prêt-à-porter. http://www.20minutes.fr/societe/1730987-20151127-attentats-paris-victimes-france-ailleurs-12

“Je rouvrirai La Belle Equipe, et les rires reprendront leur droit. Quoi qu’il arrive, et jusqu’à ma mort, ce lieu sera un lieu de vie.”

Grégory Reibenberg, husband of Djamila Houd and owner of La Belle Equipe.

La Belle Equipe

Café, bar et restaurant au cadre cosy proposant une carte de cocktails et une ardoise bistrotière soignée.

Adresse : 92 Rue de Charonne, 75011 Paris

Téléphone : 01 43 71 89 58

Horaires : Ouvert aujourd’hui · 08:00–02:00

**************************

Remembering Nohemi Gonzalez, a Year Later

Nov. 13 is the one-year anniversary of the death of Nohemi Gonzalez, the only American among 130 killed in the terrorist attacks in Paris.

Nohemi was on a semester abroad, trading in 15 weeks at California State University, Long Beach, for an experience at Strate School of Design in Sèvres, outside of Paris. She was the first in her family to attend college — a Mexican-American industrial design student on her way to becoming one of just over 15 percent of young Hispanics who hold a bachelor’s degree.

On the night she was killed, she was enjoying the City of Light like a Parisienne, in a lively bistro on Rue de Charonne, perhaps toasting her Cal State design team, which, she had just learned, placed second in a competition for efficient packaging of snack food. The packaging would decompose, leaving no trace behind.

It is hard to truly know this student from public comments. The language of grief exalts and reduces the dead with larger-than-life words. She is described by friends as “always happy,” “beautiful” and “a bright spirit.” Her own Facebook posts give a sense of a more particular Nohemi: “Learning a 3D modeling computer program in a language I don’t know is up there in the top three hardest things I’ve ever had to do.” (The reader can’t help but wonder what the other two hard things were.)

In interviews soon after the attack, Nohemi’s mother sometimes used the present tense to describe her daughter: “She loves school,” she said, adding that “Nohemi wanted a different life from most of our people who just go to work and come home. She wanted a career.”

Reading about Nohemi’s short life reminded me of many of my students at Johnson State College in Vermont, where I recently retired as president. Vermont is as different from California in its demographic makeup, size and economy as two states can be, and yet her story could have been theirs. Some of my students had never held a passport or even left our state; like Nohemi, they took their first plane rides while in college, exiting wide-eyed onto foreign lands.

“I can go anywhere now,” one student told me after returning from Greece, as stunned as she was newly confident. Finding your way home on the metro in another country is one thing; doing so on your first metro ride ever is a triumph.

Like Johnson State, Cal State Long Beach is one of 400 regional colleges and universities educating 40 percent of the nation’s undergraduates. These “middle children” of public higher education — not a community college, not a state flagship — are oft-forgotten (and seldom celebrated) microcosms of their states. Nohemi might have thrived anywhere, but Cal State Long Beach, whose enrollment is 95 percent Californian and more than one-third Hispanic, seems to have fostered a keen awareness and responsibility of place (her place) and given her not only a context in which to flourish, but also the confidence to venture beyond its borders.

Nohemi had only begun her journey, but her sense of adventure might serve as a beacon for young people with limited family resources as they set out to discover worlds apart from their own.

In some ways, she was a typical study-abroad student. According to the Institute for International Education’s Open Doors report, of the 304,500 Americans who studied in another country in 2013-14, 67 percent were women. Approximately 21,000 students, or 7 percent, were focused on fine or applied art.

In other ways she was atypical: Nearly 75 percent of Americans who study overseas are non-Hispanic white, and disproportionately from private schools. Despite the opening up of federal financial aid to support study abroad, international study is still more available to students with greater family resources.

Nohemi would have beaten many odds, and we root for people who defy statistics and set new paths. Will Cal State students follow hers? I asked Dean Jeet Joshee, who oversees international study at the university, if he was seeing any drop in interest in study abroad since her death. He said that students tell him they will not be deterred from their plans.

Of course, study abroad is not without its risks. Foreign students in Rome are frequent targets of robberies, including one last summer that ended in the death of an American student in an exchange program at John Cabot University. But such highly publicized deaths may skew our perceptions.

The president of the Institute for International Education, Allan E. Goodman, has often said that getting to the airport in the United States may be the most dangerous part of studying abroad. Paradoxically, he says, he is asked by parents from other countries if they should keep their children from coming here to avoid the risks inherent in a country in which guns are rampant.

Indeed, students are about twice as likely to die at their home campuses than in another country, according to the Forum on Education Abroad, which established a database of incidents in 2014. That year, 313 incidents were reported, 80 percent of them an illness; gastrointestinal ailments were a major culprit. Four deaths — two accidental, two from pre-existing medical conditions — were also reported by study-abroad insurance providers. The 2015 incidents report will include Nohemi Gonzalez’s death.

As unlikely as Nohemi’s death was, it was not random. Her assassins did not set out to kill a Mexican-American design student in particular, but they did set out to murder what she represents: the freedom of pleasure, choice and agency.

Colleges are brave institutions. They must be part of the forces that shape the lives of young adults during their most alert and seeking years. As parents and educators, it’s our job to ensure that we protect these freedoms for our young people — here, at home — and instill in them the values and responsibilities that such liberties require. Then we can set them free, and hope it’s enough.

Most students who return from a semester or more of international study report greater maturity and a clearer understanding of their own values.

Living and learning in another culture is more important than ever — for the individual students, of course, but also because the empathy such experiences foster is crucial in maintaining a safer, more loving world. No other single experience comes as close to building a new perspective on citizenship and place as study in another country. Nothing.

Nohemi’s brief immersion in that experience made her life, I am convinced, a larger one. This was a woman who refused to be constrained by tradition or circumstance. She chose knowledge instead of ignorance. She chose to imagine a future for herself.

That she did not get to inhabit that future breaks our hearts but not our resolve to leave our homes and expand our notion of citizenship and belonging.